Among the most frequently called-upon of audio effects, delay is an essential component in every producer’s mixing arsenal. Whether you’re looking to add enriching echoes to a vocal, energise a percussion line or turn a guitar riff into an evocative soundscape, there’s an endless array of delay plugins out there with which to do it, from virtual emulations of vintage hardware devices to inventive new software designs that couldn’t exist in the real world. Nevertheless, in terms of the fundamentals, the vast majority of delay effects fall neatly within a very finite range of well-established technological categories and operational styles – let’s turn on the taps…

Tape delay

The original echo effect, a tape delay (or plugin emulation thereof) works by recording the input signal to a loop of reel-to-reel tape, which then passes through one or more play heads, with the speed of the tape (in conjunction with the distance between the record and play heads) determining the delay time. An erase head placed after the play head(s) then wipes the tape, ready for the next looping cycle. A tape delay unit will likely also feature a feedback control, which routes the output back to the input by a user variable amount, thereby causing the echoes to multiply until, if left unchecked, they build up to the sort of howling, extended ‘echo-scapes’ often heard in dub and techno.

For today’s producer, the main appeal of tape delays in comparison to their seemingly more capable digital counterparts is, quite simply, the sound and performance/automation angle they bring to the table. The warmth of tape – be it real or emulated – never fails to please the ear, and the pitchshifting that occurs when the tape speed is changed or modulated on the fly has its own creative uses, as ably demonstrated by the wobbly textures of synthwave, IDM and other such genres.

Bucket brigade delay

Invented as a less finicky, more portable alternative to tape, the analogue bucket brigade delay, or BBD, passes the input signal through a series of switched capacitors in order to delay its playback. The signal is forwarded through the capacitor array like water poured from bucket to bucket down a line of hose-less firemen, and the delay time (ie, the speed of transfer from capacitor to capacitor) is governed by a master clock control. The decidedly gritty character of the sound comes from the degradation of the signal as it travels through the capacitors, and a BBD pedal or plugin emulation is great to have around for those occasions when only a truly dirty, lo-fi echo effect will do.

Digital delay

The advent of digital signal processing in the 1970s heralded a paradigm shift in recording studio technology that saw, amongst many other disruptions, tape and analogue delay units around the globe replaced by more compact, reliable and sonically spectacular digital models. By converting an incoming analogue signal into a digital data stream for sample-accurate delay processing prior to conversion back to an analogue output signal, digital delays eschew the warmth, saturation and fizz of their tape and BBD ancestors for hi-fi cleanliness, unmatched functional convenience and accuracy, and greater flexibility in the parameters available and their ease of adjustment.

When it first arrived on the scene, digital delay felt like the future, surely destined to relegate its forebears to the annals of history. In actuality, though, tape, BBD and digital delay types have all endured on their own individual merits, which is why you’ll find so many amazing plugin emulations of all of them on the market today.

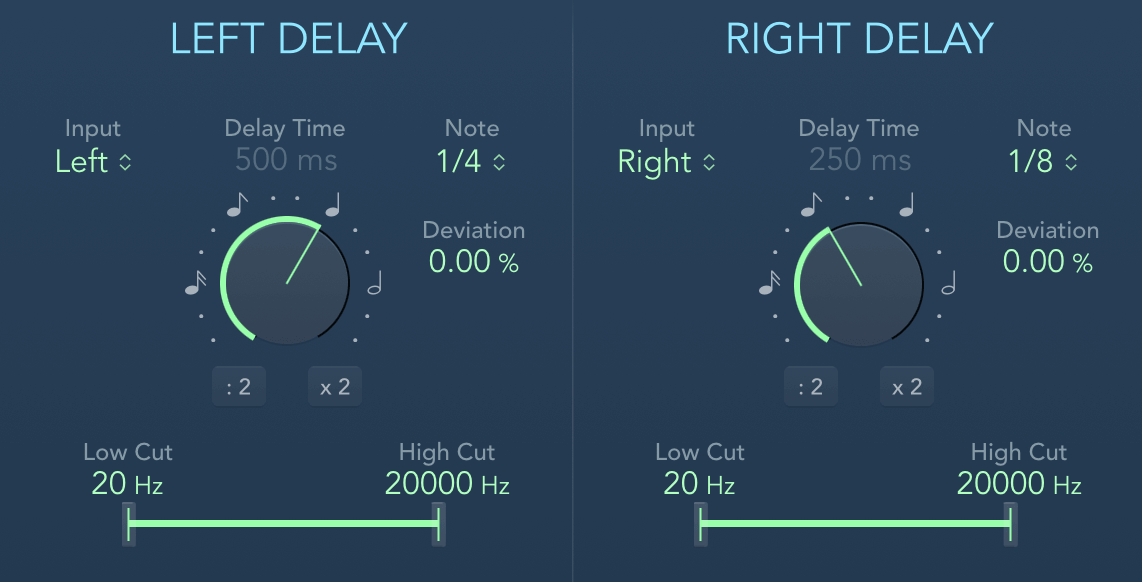

Stereo delay

The default behaviour of most non-specialist delay plugins (ie, those included in your DAW, and/or offering multiple modes of operation), a stereo delay enables independent delay times to be dialled in for the left and right stereo channels, to generate spatially differentiated echoes. You could have, say, an eighth-note triplet delay on the left channel and a quarter-note on the right, yielding a groovy panoramic cross-rhythm when the feedback is raised; or set very short delay times (15ms and 40ms, for example) and crank the feedback right up for sproing-y reverb-style effects.

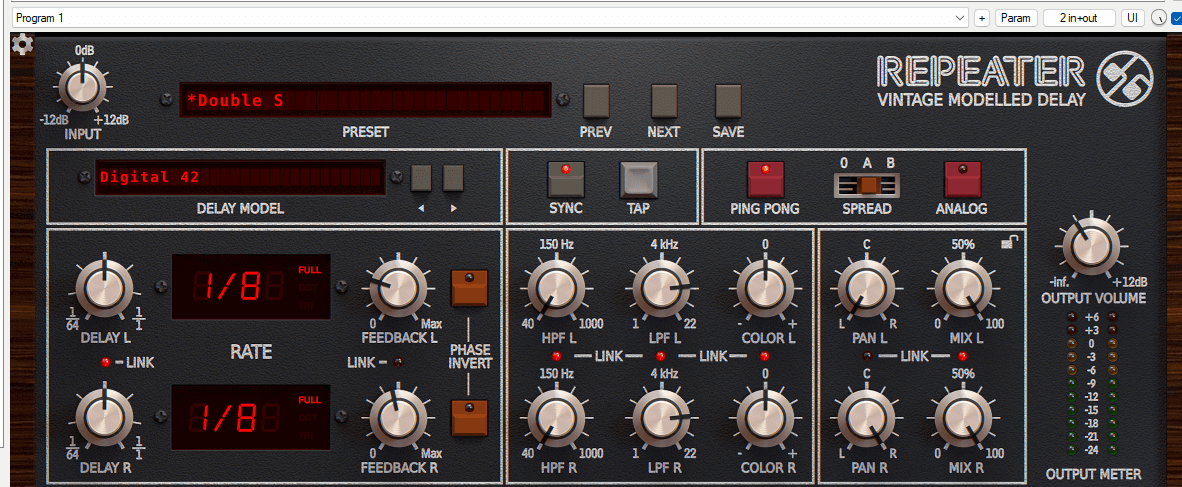

Ping-pong delay

Another form of stereo delay, the ping-pong delay comprises separate mono delay lines for the left and right channels, each featuring its own delay time control and feeding into the input of the other. So, the input signal enters the left or right channel, where it’s delayed by the specified time before being sent in parallel to the output of the effect and the opposite delay line, the latter delaying it again by its specified amount. With the left channel set to 150ms and the right set to 200ms, for example, you’ll hear the left delay (‘ping’) 150ms after the input, and the right delay (‘pong’) 350ms after the input (200ms + 150ms). As you may have surmised, ping-pong delay is the type to reach for when you want your echoes to bounce between the two sides of the stereo field.

Multi-tap delay

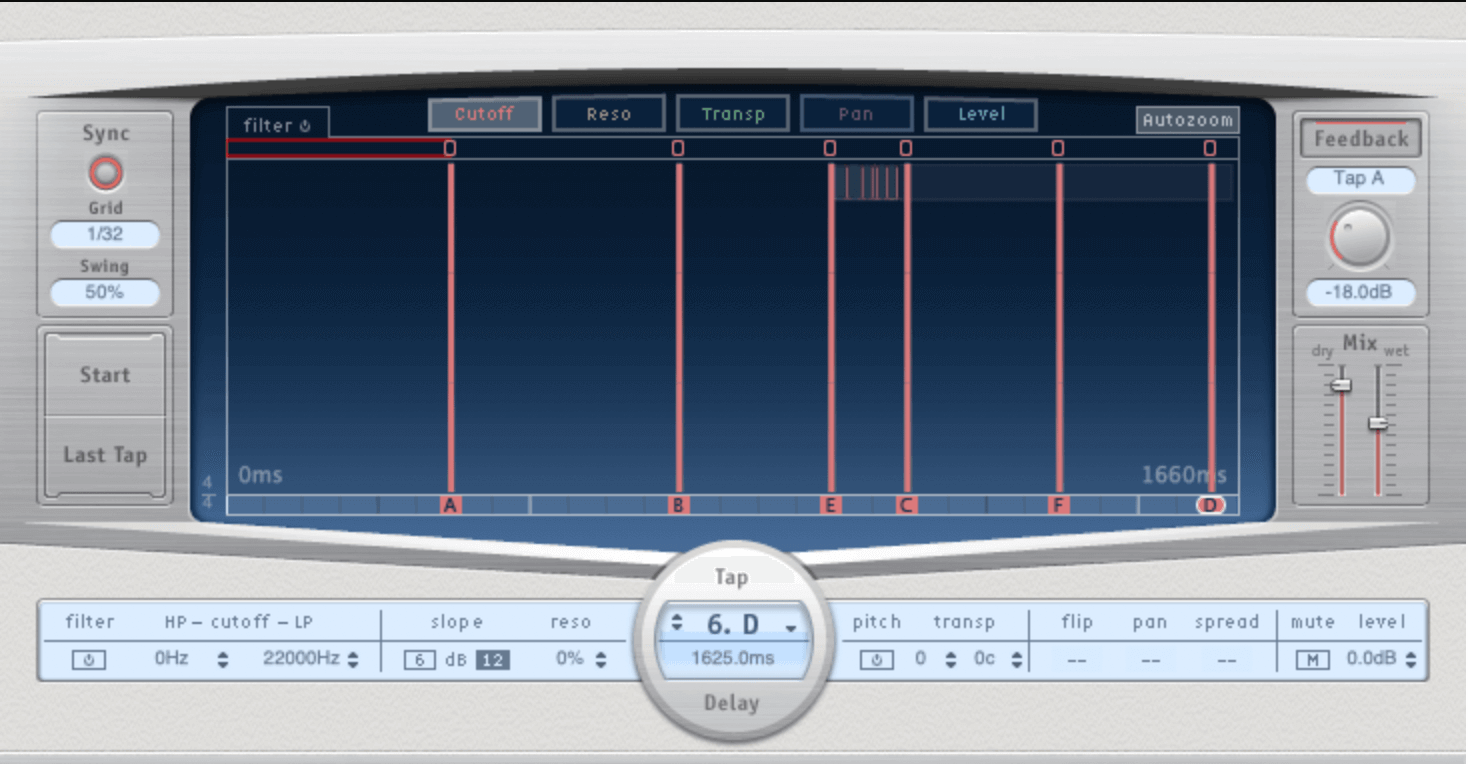

Although any delay effect with more than one repeat (or ‘tap’) clearly qualifies for the title ‘multi-tap’, the generally accepted definition of the term is a delay module or plugin that offers more than two independently configurable delay lines, with per-tap parameters including delay time, volume level, pan, feedback and, often, filtering. With anywhere up to eight taps in play, a multi-tap delay gives you total freedom to design your own intricate rhythmic echo sequences, with no limits on their temporal irregularity and complexity – just the thing for turning a single shaker hit into a busy percussion line, or conjuring a funky rhythm guitar or synth riff from a single note or chord.

Delay-based derivatives

Finally, we should point out that delay lines are in fact called on in music production for far more than just creating discrete echoes. Referred to as ‘delay-based’ effects, chorusing, flanging, phasing and even algorithmic reverb all draw on varying numbers of very short modulated delays in the application of their respective processes. Amazing what the simple duplicating and offsetting of an audio signal from its original position can do, right?

Our Products

-

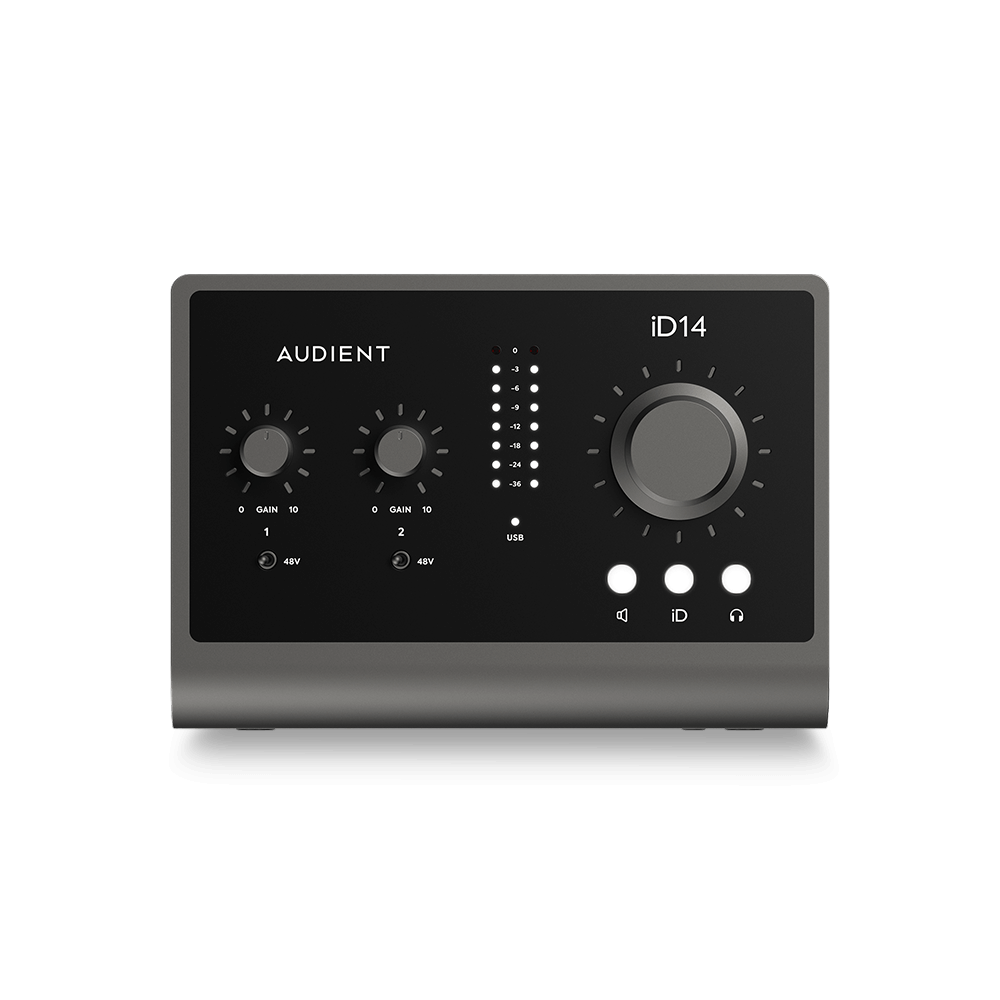

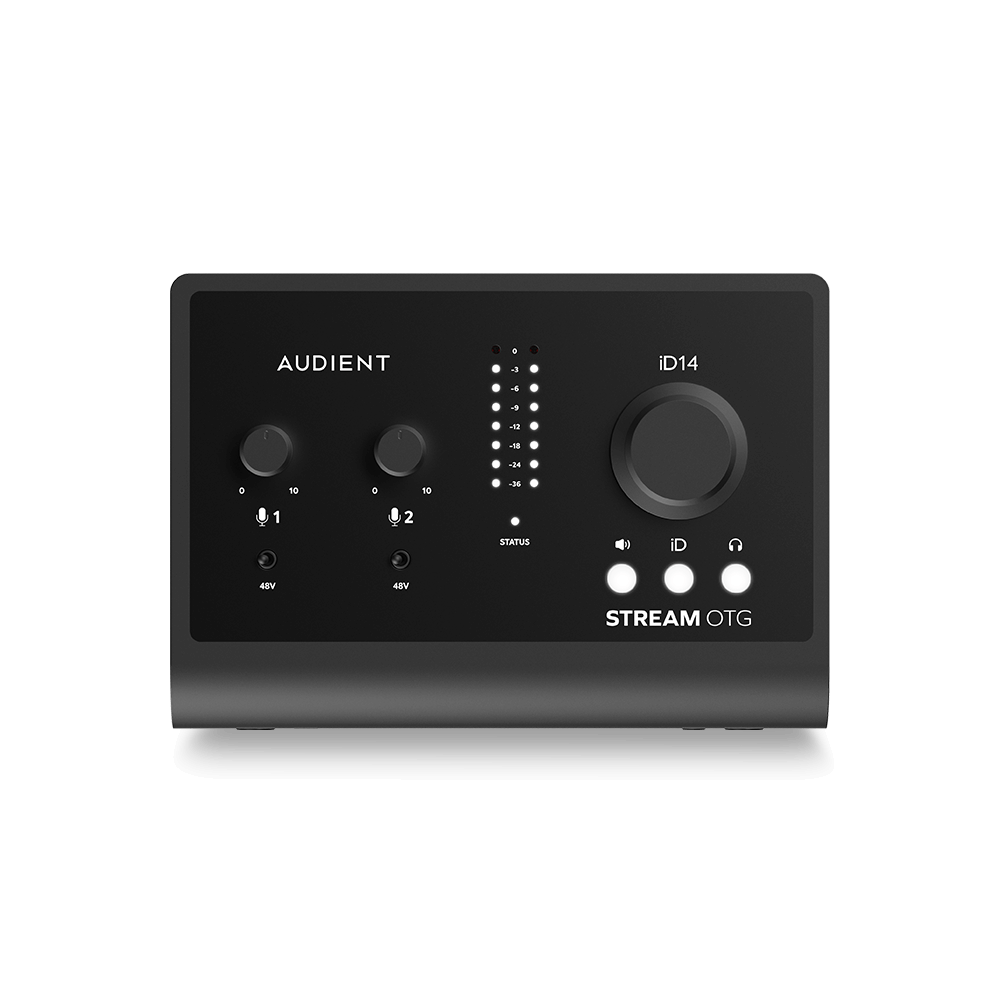

2输入 | 2输出 音频接口

-

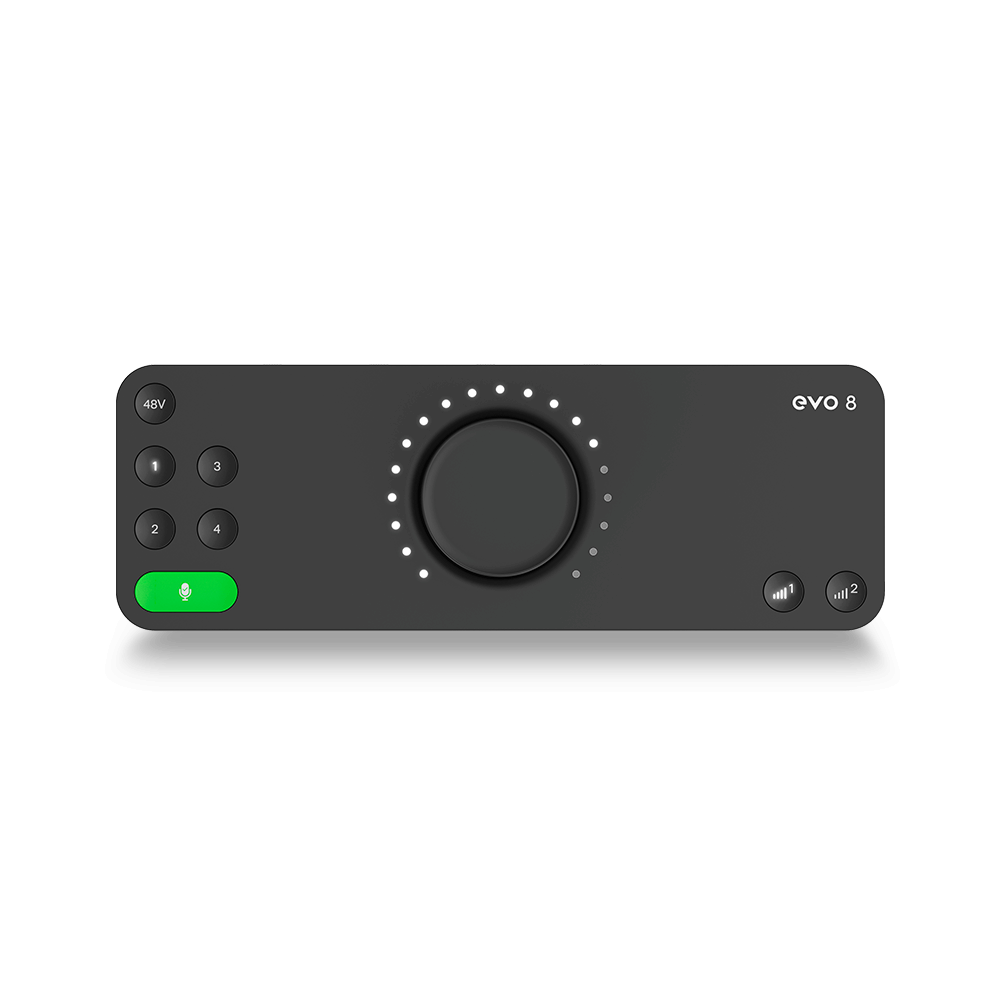

10输入 | 6输出 音频接口

-

6输入 | 4输出 音频接口

-

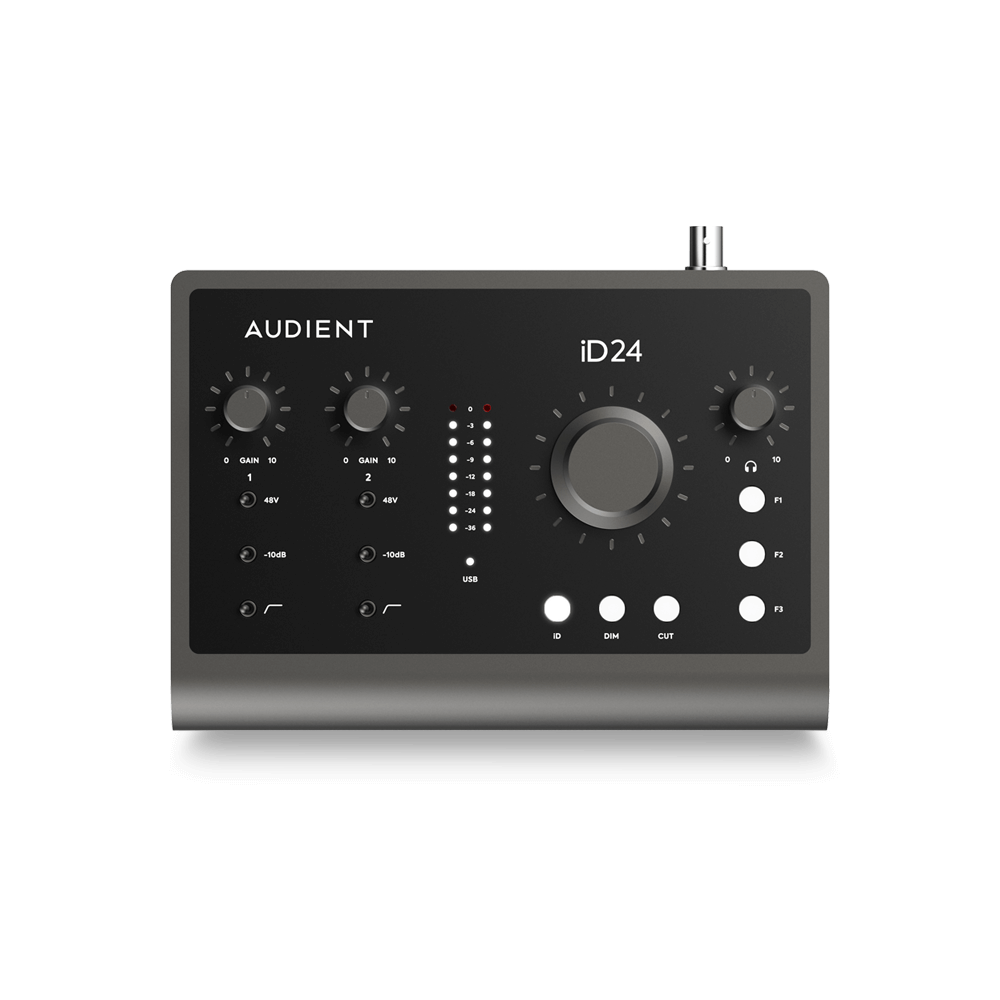

14输入 | 8输出 音频接口

-

10输入 | 14输出 音频接口

-

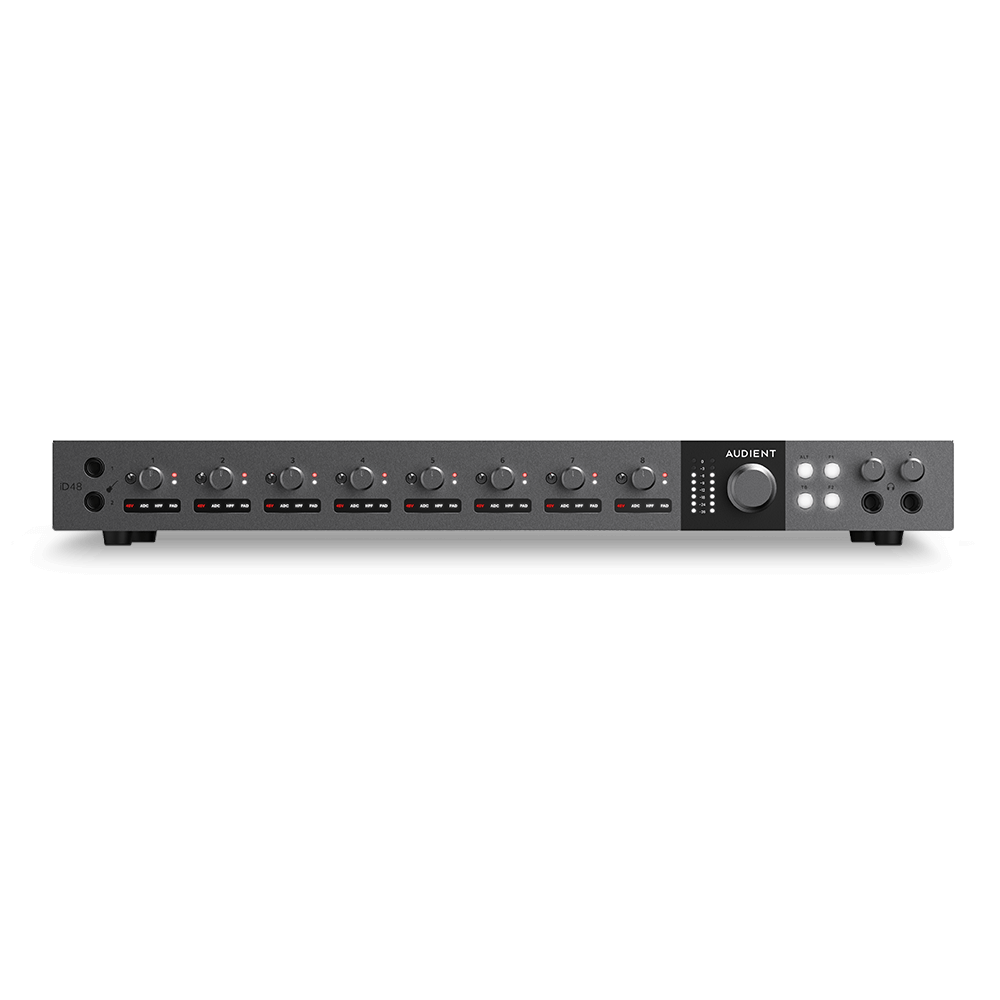

20输入 | 24输出 音频接口

-

24输入 | 32输出 音频接口

-

10输入 | 14输出 音频接口

-

10输入 | 4输出 音频接口

-

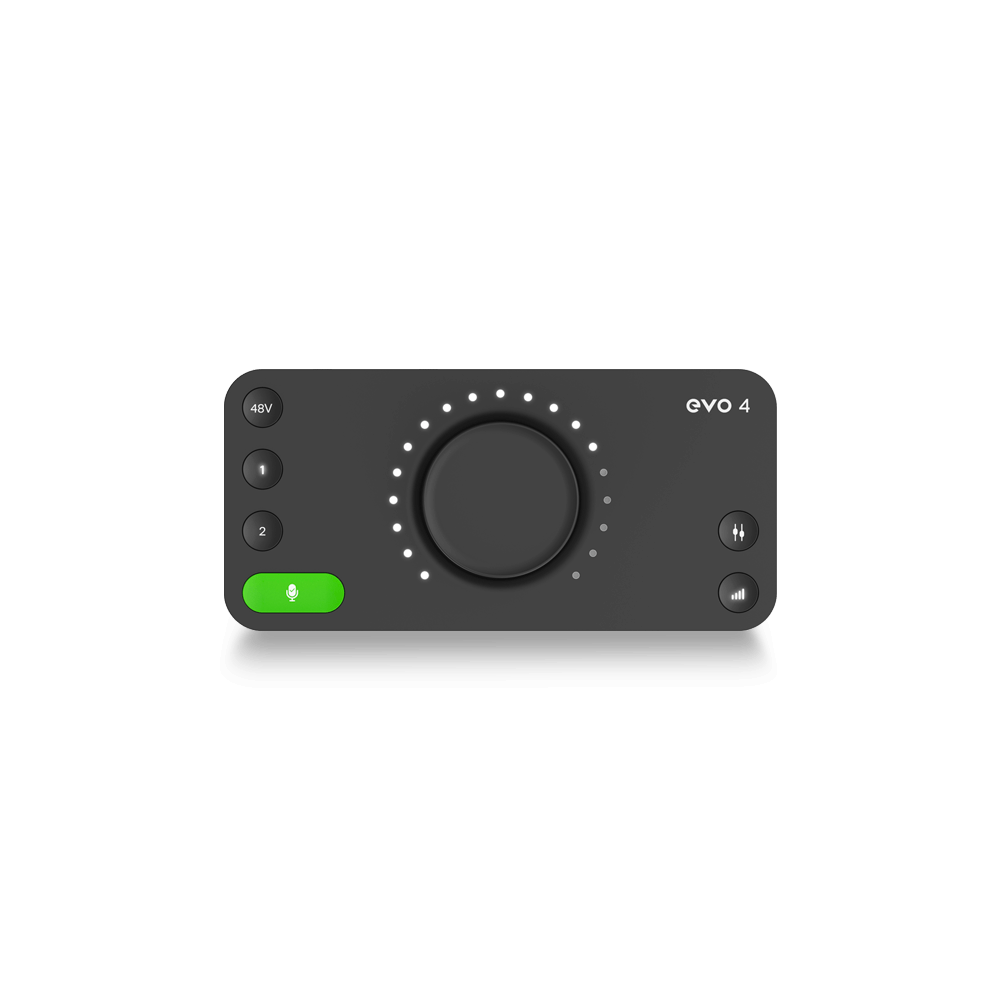

2输入 | 2输出 音频接口

-

4输入 | 4输出 音频接口

-

24输入 | 24输出 音频接口

-

开始录音所需的一切

-

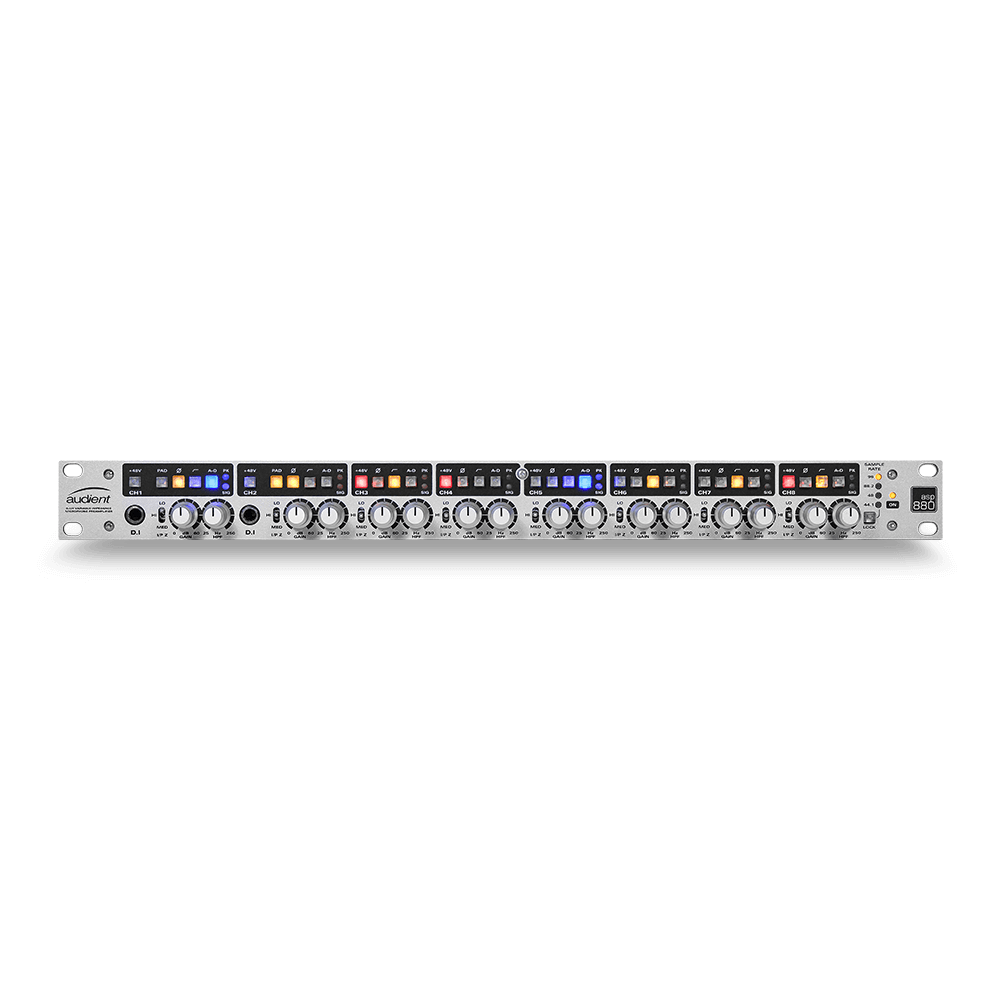

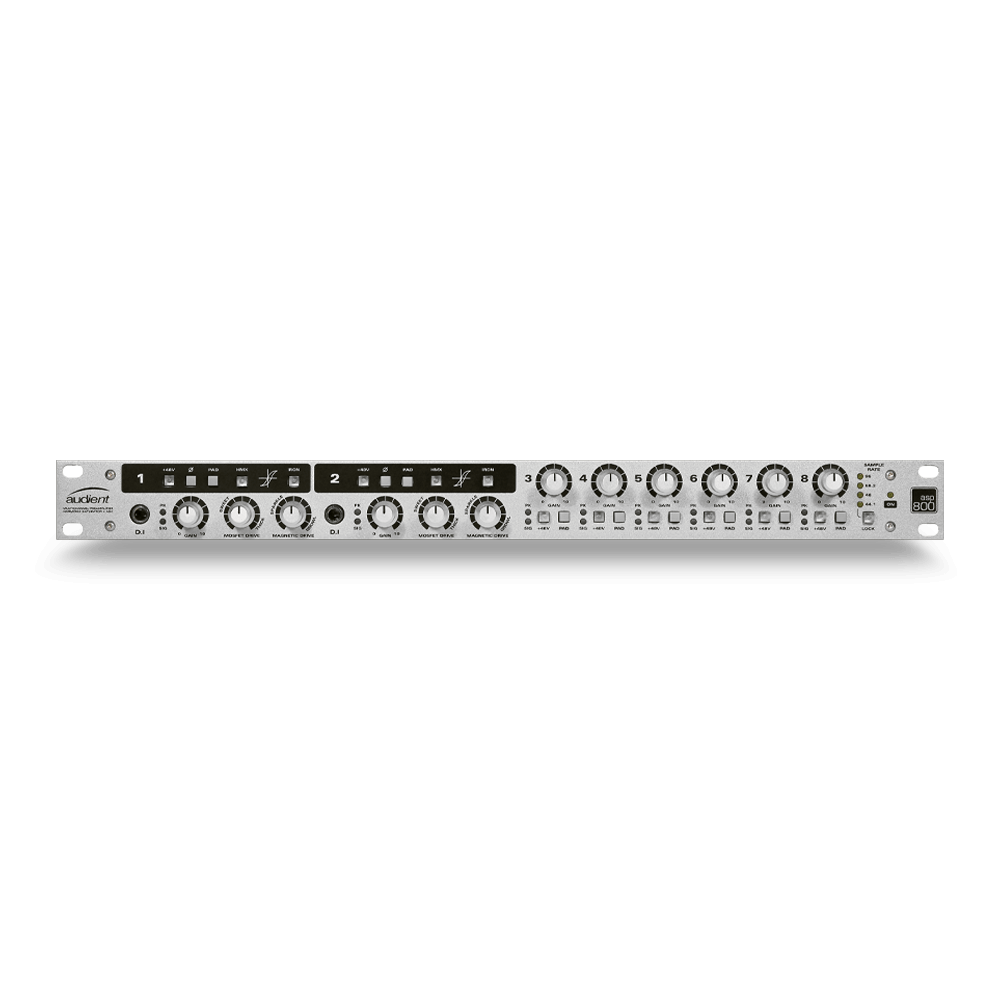

8 通道智能前置放大器带 AD/DA

-

具有ADC的8通道麦克风前置放大器

-

具有 HMX 和 IRON 的 8 通道麦克风前置放大器

-

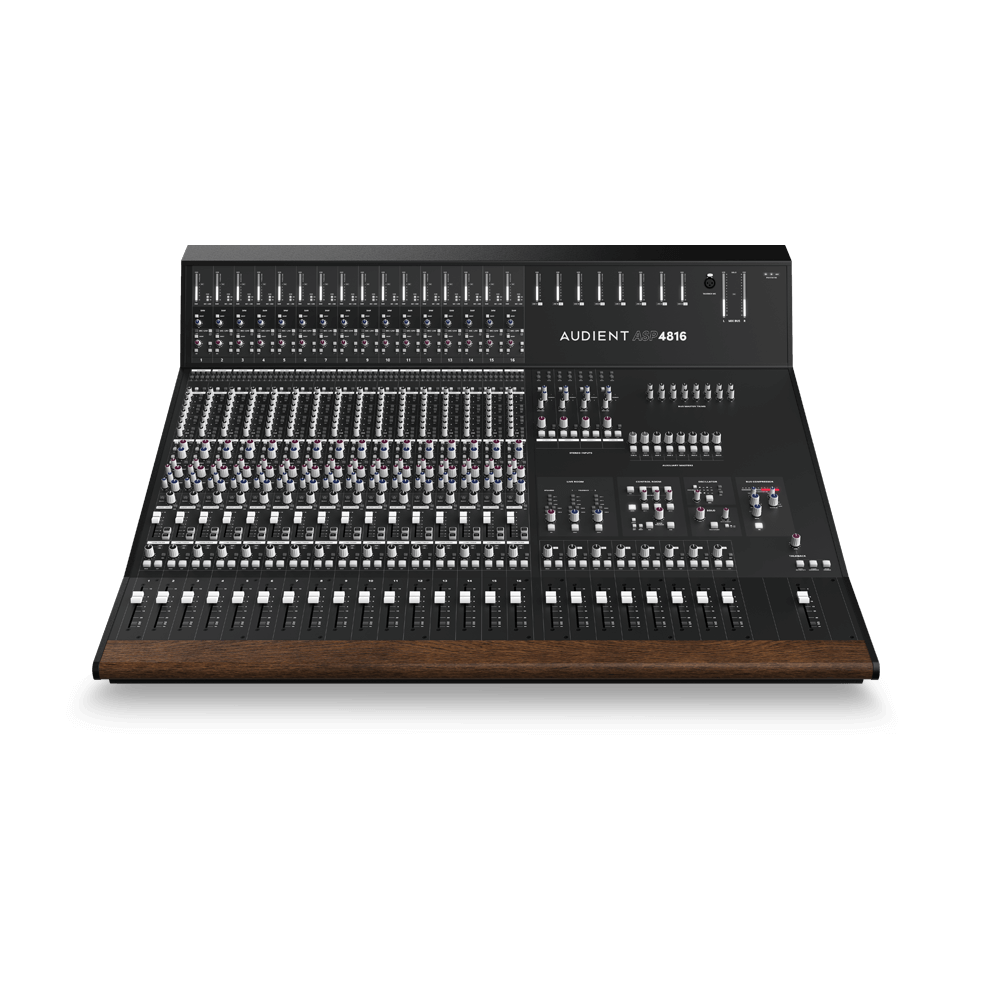

大型录音控制台

-

小型模拟录音控制台

-

小型模拟录音控制台

-

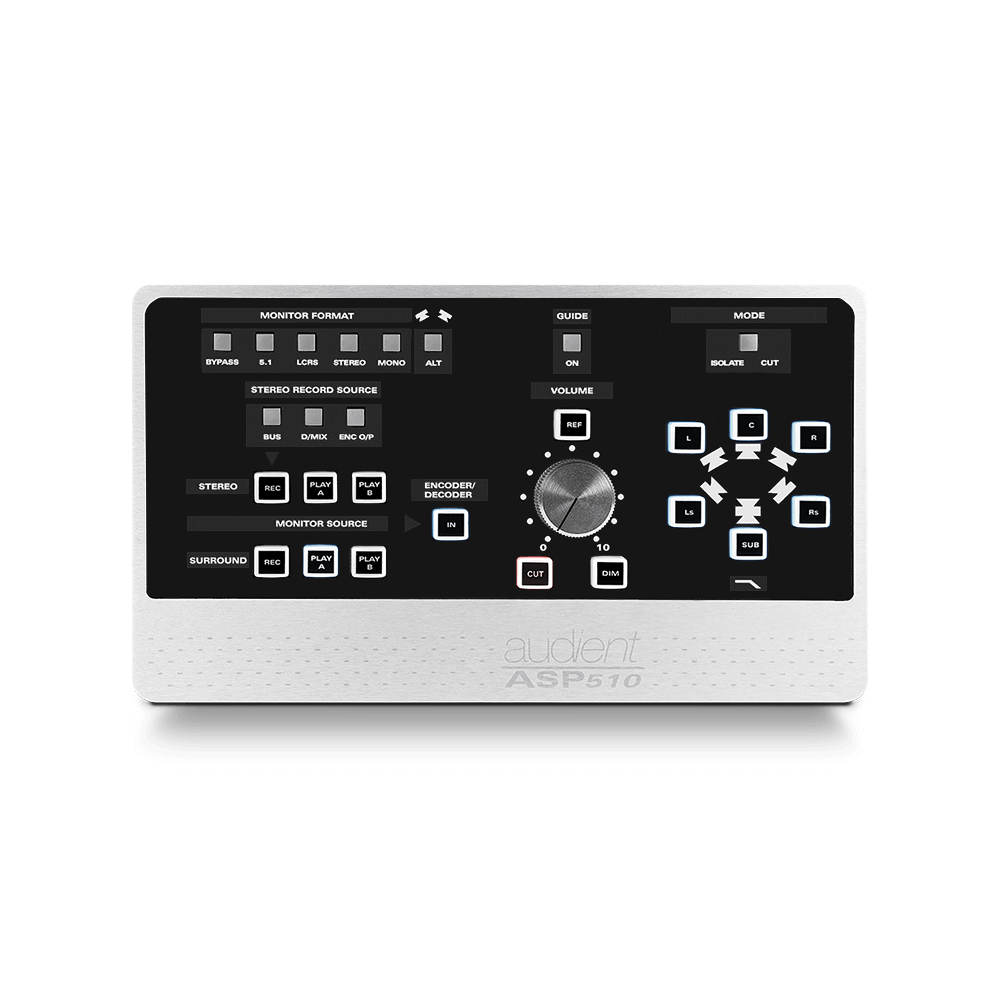

沉浸式音频接口与监听控制器

-

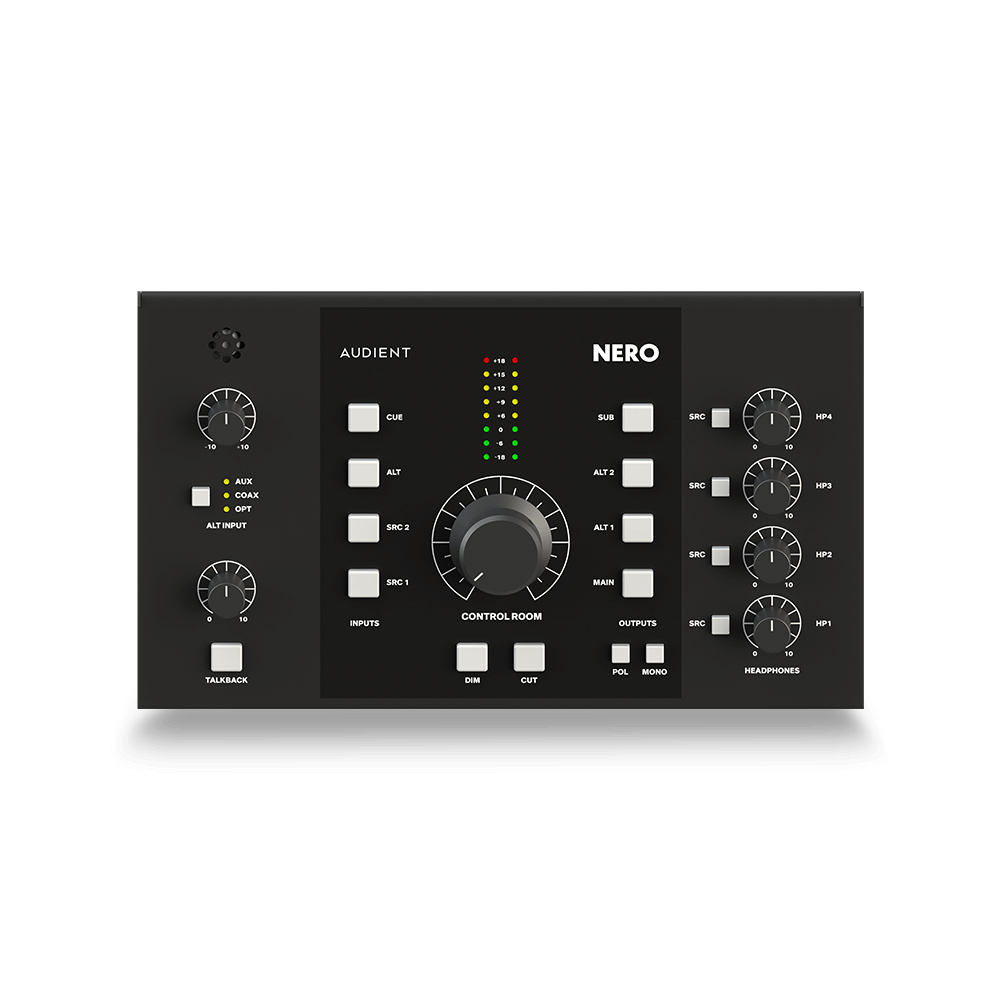

桌面监听控制器

-

环绕声控制器